"Lost in Translation" | Analyzing an Art Film from the Perspective of Linguistics and Cross-cultural Communication

Table of Contents

“Lost in Translation” is a film directed by Sofia Coppola, telling the story of a middle-aged actor in crisis and a young woman in a quarter-life crisis who meet in Tokyo and spend time together. In this film, the director showcases some characteristics of Japanese culture and potential misunderstandings and conflicts that may arise in cross-cultural communication through the dialogue and behavior of the male and female protagonists. This article analyzes some details in the film from the perspective of linguistics and cross-cultural communication, exploring the cultural phenomena in the film, as well as the director’s understanding of and conflicts with Japanese culture. (This article is a reorganized version of my case study assignment for the Crossculture Communication elective course during my undergraduate studies.)

##

Introduction

The entire film is set in Tokyo, further permeated with a Japanese-style atmosphere of loneliness.

The director of this film is Sofia Coppola, whose talent is always overshadowed by her father, Francis Ford Coppola, the director of “The Godfather” trilogy. However, as a female director, when filming “Lost in Translation,” she incorporated her experience of living in Tokyo when she was young, projecting her own experiences into the film’s story in a semi-autobiographical form.

The Chinese translation of this film’s title is somewhat regrettable. Its English name is “Lost in Translation,” and the protagonists’ sense of being lost is not only about being in a foreign country or having language issues but more about the confusion and melancholy in the mutual understanding between husband and wife, men and women, friends, and even between the self and others. Personally, I feel that “Lost in Translation” has a bit more depth than the Chinese title “Lost in Tokyo.”

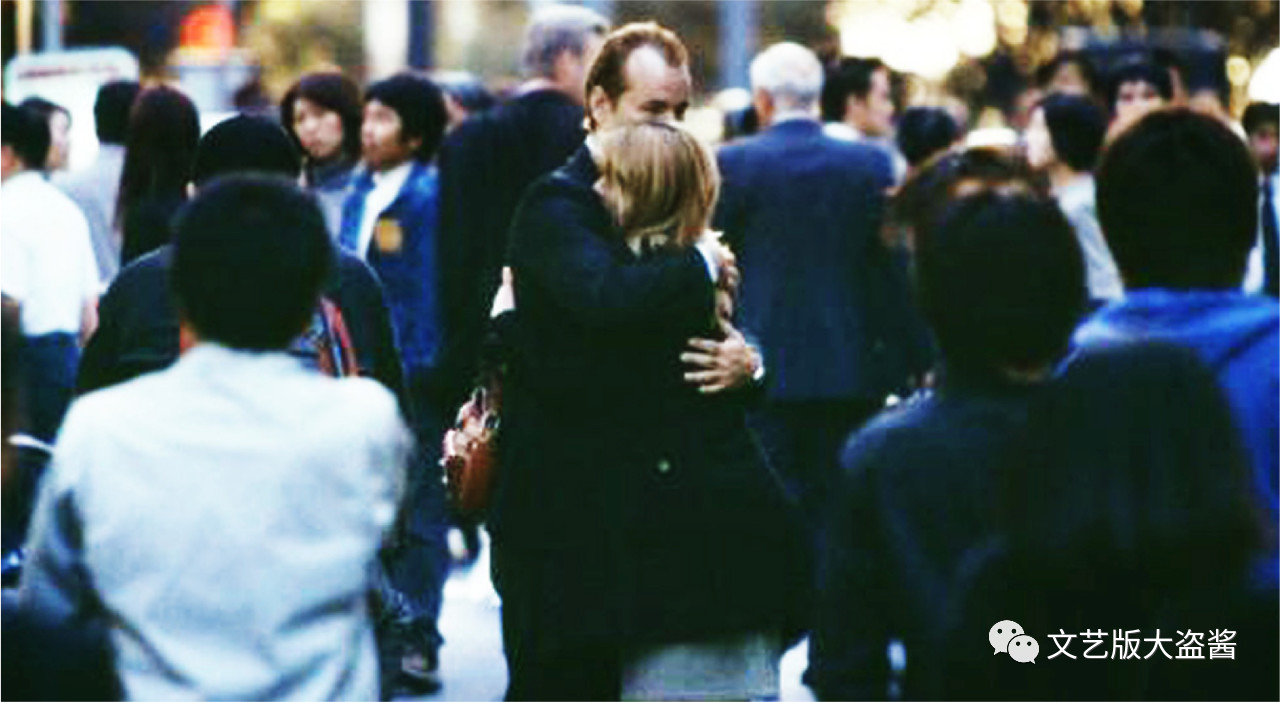

Perhaps the two stills that best convey the atmosphere of this film are these.

##

Lost in cityviews

1. Scarlett’s character sitting on the bed looking out the window

In contrast to the nighttime Tokyo, the morning Tokyo outside the window is clear and ethereal. Scarlett, sitting on the windowsill in her pajamas, looks very depressed. (Although it has to be admitted that taking photos in front of the floor-to-ceiling windows on the high floors of this Park Hyatt Hotel has become a standard pose for internet celebrities.)

2. The male lead in front of Shibuya Station

This still does not appear in the movie but is used for the movie poster promotion. The male lead has a collage-like feeling in the center, and in contrast to the daytime, the lights of the high-rise buildings and roads in the background present a gloomy tone, further highlighting the male lead’s eerie feeling of not knowing where he is.

##

Lost in Japanese

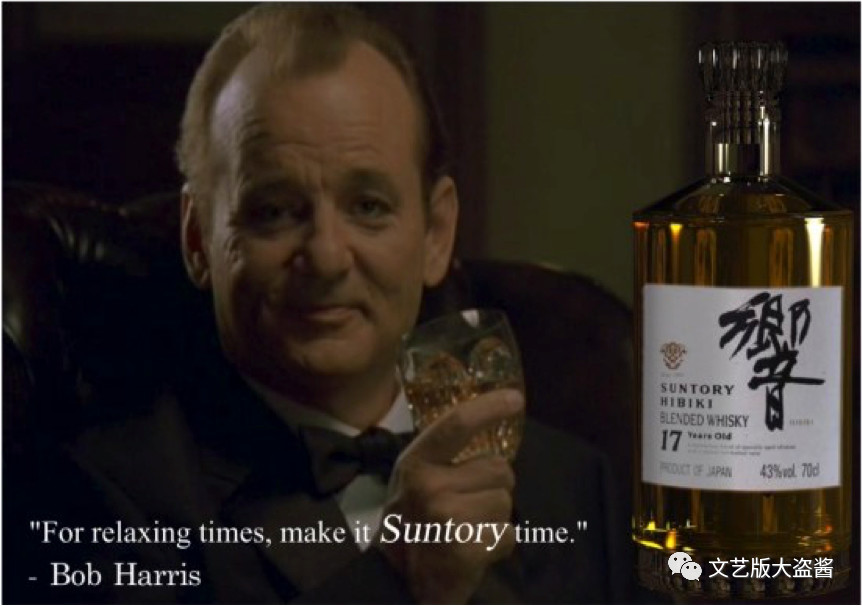

The male protagonist of the story is a has-been actor going through a midlife crisis, and he comes to Tokyo to shoot a commercial for Suntory whiskey.

Although the slogan in the commercial is “For relaxing time, make it Suntory time,” the male lead is not at ease during the shooting process.

During the shoot, the entire crew is Japanese, and there is a translator with broken English.

The director says, 「感情を込めて、古い友だちと合うように、ゆっくり話す…」, giving very detailed instructions (speak slowly with emotion, as if meeting an old friend).

However, the translator only translates to the male lead, “to turn, look the camera”.

When the male lead is very puzzled as to why he is only given such simple instructions, he asks the translator, “Do u want me to turn from the right or the left?”

However, the translator says a very long string, 「彼の方はもう準備できています。で、スタートがかかったときに、カメラのほうに、右側から振り向けるか、それとも左側か。そのへんいかがなさいますでしょうか?」 (He is already prepared, but when the shooting starts, should he turn his head towards the camera from the right side or the left side? What is your opinion on this matter? *The 高見 here is because the translator used the advanced honorific いかがなさいますでしょうか lol.)

However, there’s a small detail here: when the director repeatedly explained his photography requirements, he used many “horizontal letter words” (foreign loanwords), such as:

| Japanese and meaning | English |

|---|---|

| ハイテンション (heightened emotion) | high tension |

| パッション (passion) | passion |

| ジェントリー (gently) | gently |

| インテンシティ (forcefully - note: this is a mistranslation where the noun is incorrectly used as an adjective) | intensity |

##

Fun fact

Let me explain some basic Japanese language knowledge for readers unfamiliar with linguistics and Japanese.

From a character perspective, Japanese consists of three writing systems: kanji, kana, and romaji. Kanji includes simplified characters, traditional characters, and Japanese-style kanji. Kana is divided into hiragana and katakana (romaji refers to the Latin alphabet).

From a word perspective, loanwords come from other languages and are written in katakana for phonetic representation, with the characters themselves carrying no inherent meaning. In contrast, kanji are ideographic characters that carry specific meanings. For example, the above パッション (passion, pronounced “passhon”) is an English loanword written in katakana, while the equivalent 情熱 (jounetsu) uses kanji characters that give you a good idea of the meaning just by looking at them.

Why are foreign words called “horizontal letter words”? Before the Edo period, Japan, like China, primarily wrote kanji vertically (known as kanbun). Later, influenced by foreign cultures, writing horizontally became common. It was precisely this arrival of foreign culture that enriched Japanese with more loanwords (during the Meiji period, loanwords were initially called “Western words,” but since words from China and Korea were technically also foreign, the term was changed to “loanwords”). Therefore, loanwords came to be called “horizontal letter words.”

Back to the film.

In any case, this advertisement filming scene is a complete disaster.

It’s worth noting that not just in this scene, but throughout the entire film, all Japanese spoken by Japanese people and English dialogues have no subtitles (I’ve seen both the English-subtitled and Japanese-subtitled versions). This was actually intentional. To enhance the viewing experience and convey the sense of being lost and lonely that the film wants to express, they deliberately chose not to add any subtitles whether the film was shown in Japan or overseas.

This is a very bold and risky move. It’s like saying, “If you can understand, you understand; if you can’t, you can’t.” This is a very artistic approach. It’s also a way to express the director’s attitude towards cross-cultural communication and the theme of the film.

There’s another very awkward scene in the film that’s also related to language. When the Japanese side arranges a call girl to visit the male protagonist’s room, he’s completely unwilling, but this lady enthusiastically says to him in broken Japanese-English: “lip my stocking”.

Lip??

Actually, she meant to say “Rip my stocking”. (The subtitle translation above is quite good)

Because Japanese pronunciation lacks rolled R sounds, unless they grew up abroad, Japanese people generally cannot pronounce R, including sounds like /r/,/ɚ/,/ɑr/,/ɔr/,/ɛr/.

During my college phonetics class, my professor mentioned an experiment involving Japanese native speakers and English native speakers. The subjects had to bite a chopstick while pronouncing the 26 English letters and the Japanese 50 sounds. The results showed that Japanese native speakers could pronounce all 50 Japanese sounds while biting the chopstick, but neither Japanese nor English speakers could keep the chopstick in place when pronouncing English sounds. This proves that Japanese is one of the languages requiring minimal lip, tongue, and mouth muscle movement.

Therefore, Japanese people who learn Japanese from childhood have difficulty pronouncing sounds outside the 50 sounds because those pronunciation muscles never developed and gradually weakened from lack of use, making their pronunciation flat and non-standard. This issue is playfully brought up in the film when the main characters are drunk.

-Why do they switch the “R"s and the “L"s here?

-… just mix it up. They have to amuse themselves, because we are not making lots of laughs.

##

Lost in Culture

The film contains many small details that reflect aspects of Japanese culture.

Salary men in suits and ties crowded in an elevator.

At the sushi restaurant, when the male protagonist notices the female protagonist’s injured foot, he immediately asks to look at it. The sushi chef shows an uncomfortable expression.

In Japan, such behavior in public, especially in a restaurant, is very impolite. Japanese people are also quite sensitive about feet - one shouldn’t go sockless or casually show the soles of their feet to others (although Japanese people frequently remove their shoes).

This is another interesting scene where both characters are unhappily eating at a shabu-shabu restaurant, complaining about why the restaurant only provides ingredients and makes them cook the meat themselves.

The male protagonist instinctively tries to close the taxi door, but in Japan, taxi doors are automatic and controlled by the driver.

Election campaign vehicles with loud speakers that disturb the peace. During election periods, many such vehicles appear on the streets, covered with candidate posters and promotional boards. The candidate usually sits inside, broadcasting self-introductions and campaign promises at extremely high volumes.

##

Lost in Tokyo

The film contains many details showing the director’s understanding of and conflicts with Japanese culture.

However, the film’s focus remains on describing the sense of alienation between individuals and the feeling of being lost in one’s own existence.

Tokyo is truly perfect for getting lost (both literally and figuratively).

As a traveler or newcomer, you experience literal loss of direction. Tokyo is too big, public transportation is too complex, and stations like Shibuya, Shinjuku, and Ikebukuro are too large - it’s too easy to get lost.

Gradually, as you live here longer, you experience a slow, prolonged process of becoming lost. This process feels like being in the film - gazing at street scenes, moving through crowds, drinking and feeling melancholic. Finally, you realize this sense of loneliness doesn’t belong to this city or to anyone. It’s a frequency, and people here are simply tuned to that frequency.