Confused but Not Following a Teacher? | How Do We Know What We Know - The Abstraction Ladder

Table of Contents

Abstraction Ladder, first proposed by S.I. Hayakawa (1949), is a concept that outlines the rules of language, cognition, and how we express our cognition through language. It’s not only applicable in linguistics but can also help us think more deeply about various things in daily life.

The higher the level of abstraction, the easier it is to overlook individual characteristics and differences. This can lead to failure when conducting research, especially in inductive studies (I’ve been reading about grounded theory, and the abstraction ladder is very useful for reflecting on analytical validity). Or, from a more everyday perspective, when certain reports or presentations make people drowsy, it might be due to excessive levels of abstraction.

Furthermore, the concept of the abstraction ladder has made me question so-called “strategic thinking” - whether we should “see the big picture from small details” or “look at the overall situation,” how to handle individual differences, and at what level we should focus on characteristics and differences.

The relationship between language and what it represents can be illustrated using the example of a cow named “Bessie.” Bessie is a living being, constantly changing, taking in food and air, transforming them, and expelling waste. Her blood circulates, her nerves transmit information. Microscopically, she’s a collection of various blood cells, cells, and bacterial tissues. From modern physics’ perspective, she’s a perpetual dance of electrons. We can never know what she is as a whole; even if we could describe her at one moment, by the next moment, she would have completely changed, making our description incorrect. Whether it’s Bessie or anything else, we can never make a complete “it is…” description. Bessie isn’t a static “object,” but rather a dynamic process.

What we experience of Bessie is a change, and only a tiny part of Bessie’s whole: her external light and shadow, her movements and emotions, her basic physique, her voice, and the sensations we get through touching her with our senses. Moreover, based on our past experiences, we notice her resemblances to other animals we’ve previously described using the word “cow.”

##

Process of Abstracting

The “objects” we experience aren’t “things in themselves,” but rather interactions between our nervous systems (with all their imperfections) and the external world. Bessie is unique—from any angle in this universe, nothing is identical to her. However, we unconsciously abstract or select “process-Bessie” into a category of animals similar to her in characteristics, functions, and habits, classifying her as a “cow.”

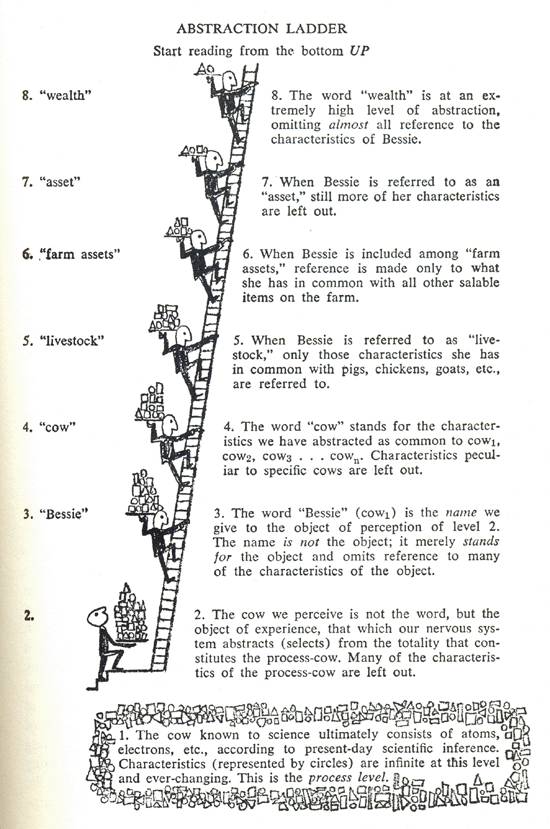

So when we say “Bessie is a cow,” we’re only noting the resemblances between “process-Bessie” and other “cows,” ignoring differences. Moreover, we’re jumping across a huge gap: from the dynamic “process-Bessie”—electronic, chemical, and neural events—to the relatively static “idea,” “concept,” or word “cow.” This relationship is illustrated in the abstraction ladder diagram.

As shown in the diagram:

Level 2: What we perceive as an “object” is the lowest level of abstraction, but it’s still an abstraction because it ignores Bessie’s characteristics in process.

Level 3: The word “Bessie” (cow 1) is the lowest linguistic level of abstraction, ignoring more characteristics—differences between yesterday’s Bessie and today’s Bessie, today’s Bessie and tomorrow’s Bessie—selecting only their similarities.

Level 4: The word “cow” only selects similarities between Bessie (cow 1), Daisy (cow 2), Rosie (cow 3), etc., so “cow” discards more characteristics than “Bessie.”

Level 5: The word “livestock” only selects or abstracts common characteristics between Bessie and pigs, poultry, goats, sheep, etc.

Level 6: The term “farm asset” abstracts common characteristics between Bessie and barns, fences, livestock, furniture, crops, tractors, etc., so it’s a very high level of abstraction.

Level 7: Asset.

Level 8: Wealth, which becomes money and numbers.

references

Hayakawa, S. I., & Hayakawa, A. R. (1990). Language in thought and action. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Hayakawa, S. I., & 大久保忠利. (1976). 思考と行動における言語: 原書第三版. 岩波書店.